Project presented in 2022 on the 41st Dyes in History and Archeology Conference in Visby

Dye tests: Adrienn Görgényi Andersdotter; Fish skin: Lotta Rahme

The focus of the tests was on dyeing with woad as it is Europe´s indigenous indigo-producing plant, even though new cultivating traditions are evolving in Europe and Japanese indigo cultivation is becoming more popular in temperate climates, even in the Northern regions, like Sweden. Many dyers prefer to plant Japanese indigo as it is easier to manage and can be grown in pots, unlike woad, which grows long taproots deep in the ground and is more suitable for field growing. We know today that Japanese indigo (Persicaria tinctoria) and true indigo (Indigofera tinctoria) produce significantly more pigment than woad.

Since 2016 I´ve been growing woad and Japanese indigo in Malmö and I have been dyeing yarn, textiles and fibres. Fish skin has become more popular, and in 2021 for Lotta´s request I made dye tests with the f ish skins that she tanned herself. Two different dyeing techniques were used with the two different tanning processes. The focus was on the traditional woad, but for comparison and because of the increased popularity, Japanese indigo was added to the fresh leaf dyeing tests.

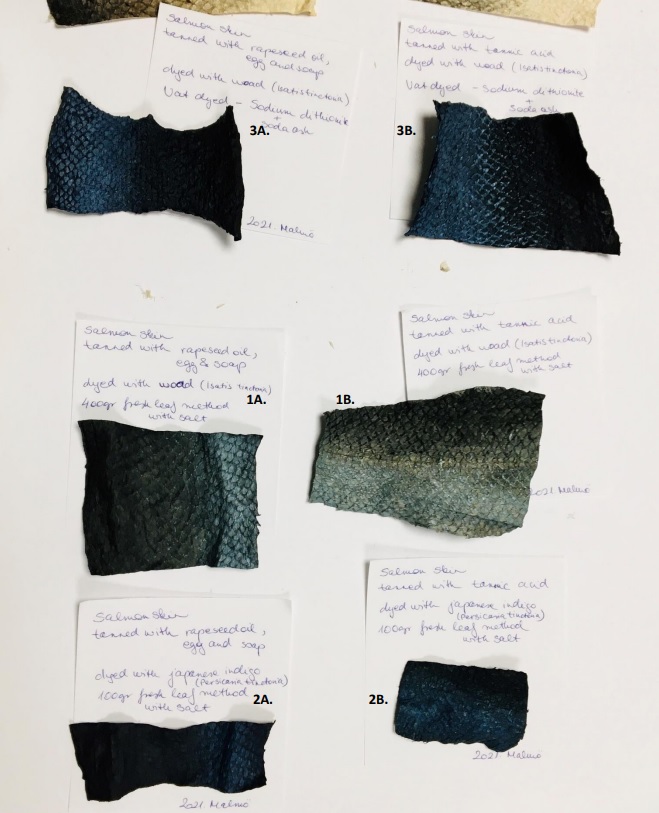

The samples

A. Farmed salmon skin tanned with rapeseed oil, egg yolk and soap

B. Farmed salmon skin tanned with gallnut

Methods:

• Method 1 – Fresh leaf dyeing with woad

• Method 2 – Fresh leaf dyeing with Japanese indigo

• Method 3 – Vat-dyeing with pigment extracted from woad

Conclusions

The test has shown us that Japanese indigo (2A., 2B.) has a lot more pigment in its leaves than woad (1A., 1B.). Woad-dyed fish skins were 2. 5 – 3.7 g in size; the Japanese indigo-dyed pieces were roughly half that size. 400 g woad leaves vs 100 g Japanese indigo leaves were used for the pieces and even if the pieces were not the same size this comparison shows the clear difference between them. T he rapeseed oil, egg yolk and soap-tanned skin (3A.) shrank somewhat during the vat-dyeing, which is likely the result of the temperature used to keep the vat active; the other piece (3B.) – tanned with gallnut – withstood the dyeing very well. Extracted pigment (3A., 3B.) gives a better control over the colour’s shade than direct fresh leaf application (1A., 1B.). Japanese indigo with the fresh leaf method (2A., 2B.) gave a similar colour shade result to the vat-dyed pieces (3A., 3B.). In this case the environmentally friendly and more sustainable method is the direct leaf application of Japanese indigo (2A., 2B.). There are no issues with chemical disposal after the dyeing and there is no prior pigment extraction needed. The leaf juice from the leftover mash can then be used to extract pigments left in it. As Japanese indigo has a higher pigment yield the amount of leaves used is lower. T he real challenge is the temperature and the pH during vat-dyeing, so the conclusion is that the fresh leaf dyeing with Japanese indigo is favourable rather than the vat dyeing with extracted pigment.